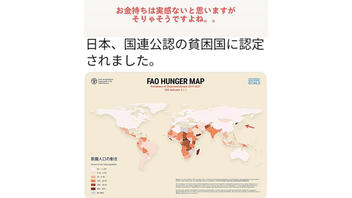

Did the United Nations (UN) recognize Japan as a poor country? No, that's not true: The UN's Prevalence of Undernourishment (PoU) survey, which provides data used to produce the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Hunger Map, does not show that Japan is undernourished. A social media post, which featured this map, falsely translates "hunger map" to mean "poor country."

The claim appeared in a video (archived here) on TikTok on April 11, 2023, with the caption (translated from Japanese to English by Lead Stories staff):

Japan has been recognized as a poor country by the United Nations.

This is what the post looked like on TikTok at the time of writing:

(Source: TikTok screenshot taken on Tue Mar 19 03:02:19 2024 UTC)

The FAO's "Hunger map" doesn't mean "poor country" in Japanese. The FAO estimates the extent of hunger in the world using the Prevalence of Undernourishment (PoU) (archived here) to measure the proportion of the population whose habitual food consumption is insufficient to provide the dietary energy levels required for a normal active and healthy life. It is expressed as a percentage. According to its latest survey, the PoU average for 2019-21 in Japan was around 2.5 percent, making it one of the lowest in Asia.

According to the FAO, hunger (archived here) is an uncomfortable or painful physical sensation caused by insufficient consumption of dietary energy.

A 2015 Summary of National Health and Nutrition Survey Results (archived here) shows the percentage of underweight people in Japan was 4.2 percent for men and 11.1 percent for women. The percentage of women in their 20s who are underweight is 22.3 percent. The percentage of people 65 and over who tend to be undernourished was 16.7 percent. However, the link between being underweight and being undernourished may not account for lifestyle choices such as overly restrictive diets and the desire to lose weight that may be carried over into old age.

The graph of Changes in Real GDP and Population (archived here) by the Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare shows that, despite the rapid growth in gross domestic product after the war, calorie intake in Japan has changed little since the war. The calorie intake of Japanese people was originally lower than that of other countries, so calorie intake has no relation to the country's economic strength.